What’s common between World War tank Blitzkrieg on the battlefronts of Europe and modern organizations’ historical fumbles with disruptive technologies

Image Source: Internet

The Blitzkrieg

Major JFC Fuller, then 37 years of age, was posted at the Somme battlefield in France at the time of WWI in 1916. On that battlefield, Major Fuller observed for the first time the awesome power of the newest savagery in the war technology, known simply as the armored tank. Major Fuller seized immediately that this new machine, the tank, holds the answer to most perplexing tactical question in modern day warfare – how to cross an open muddy field, littered with trenches and barbed wire against a haze of blazing guns? No approach had worked so far, and even hundreds of thousands of brave men laying down their lives only had as much effect as millions of raindrops washing against stone façade. But the tank held the most promise. For, it seemed indestructible, carried more firepower and could march on undeterred in all kinds of weather and most all ground conditions. Major Fuller enthusiastically sent reports of the success of this new weapon to the English war leadership. To Major Fuller, the evidence of tank’s superiority was undeniable and hence there exists every reason for tanks to replace the archaic ways of horse mounted cavalry warfare.

All the major countries in World War I (1914–1918) entered in to the conflict with cavalry forces. German forces continued the use of horses on the Eastern Front well into the war while on the Allied side, the United Kingdom used mounted infantry and cavalry charges throughout the war.

The British war leadership was steeped thoroughly in tradition and failed to see the alternate methods, regardless of the pragmatism or inevitable tide of changing times. One British General compared the faces of soldiers riding horses to those riding tanks and quipped about the lack of intelligence on the faces of tank mounted soldiers. Not just the Leadership, many soldiers on the front lines who had never seen tanks in action were at best skeptical of the new beast.

Major Fuller sought transfer to the Tank division and went on to produce brilliant papers of how to break the German lines, destroy vital rail and road links, invade deep in to the territory and strike at the German war offices. A tactical approach aided by airstrikes and resting squarely on unarguably superior technology available to the British Army in form of tank will surely make quick work of the Germans, Major Fuller conceived. By striking suddenly at the German command, the Blitzkrieg will cause the German army to disintegrate and fall. Major Fuller didn’t give up hope and continued in his efforts undeterred. In late 1917, during the battle of Cambrie, the British war leadership finally gave in to Fuller’s persistent demands and decided to use 400 tanks to attack German front lines. Unsurprisingly the British tanks decimated German defense system and made quick work of the barbed wires and shrugged off lines of soldiers firing guns at the armored plating of the tanks. A measly top speed of 4 miles per hour was enough for the tanks to run through German war lines and trenches. The Germans were caught off-guard and outmaneuvered tactically and strategically. The soldiers who saw the power of tanks for the first time were awe-stuck. In what can only be dubbed as an irony, the British Army decided to send in horses to take advantage of the gaps created by the tanks. This non-sensical move allowed German forces to regroup and drive the British back. The momentum was lost. And so was the tactical and strategic opportunity. Major Fuller once again undeterred carefully documented the events, recording what worked well and what may be improved. His ideas were reluctantly adapted and dubbed Plan 1919, to be used in the year 1919.

Major Fuller’s work did not go completely unrewarded though. For his pioneering papers in strategy work, Major Fuller received many accolades and won the Gold Medal from a prestigious think tank of the day. The most important possible beneficiary of his careful and well documented work however remained cold. The British Army continued to give Major Fuller a cold shoulder. The most brilliant and accurate strategic work in modern warfare was seen more as a threat than an opportunity.

The beliefs of British war leadership were so deep rooted that the newly formed Tank core and rapid advances in tank technology throughout the war years amounted to exactly nothing. Before Major Fuller’s plan saw the light of the day, the war ended in 1918. However, that was not the end of tank warfare or for that matter the strategy of sudden, lightning paced attacks backed by airstrikes destroying vital road and rail links that Major Fuller had conceived. Exactly twenty years later, at the start of World War II, Germany used the same Blitzkrieg approach to effectively lap up entire Europe within a matter of weeks, almost unchallenged and nearly unstoppable. Despite possessing clear technological superiority and strategical advantage of having a brilliant war strategist in Fuller, the British squabbled away the technical and strategic momentum to German forces by late 1930s. Major Fuller’s strategy proved right, not just right, in fact it was proven to be arguably the biggest breakthrough in war technology since the invention of guns.

Image Source: ideanote

How enterprises react to Innovation?

Major Fuller though is not alone, nor is the blissful ignorance of ground realities a trait reserved for British War Leadership. In 1970, the photocopying giant Xerox developed a state of the art research center in Palo Alto, California, called PARC, short for Palo Alto Research Center. PARC scientists quickly paid back Xerox by doing innovative work in laser printing that would establish Xerox as leader in printing technology for decades. Shortly thereafter Xerox scientists developed the first computer, truly ahead of its time. Steve Jobs during one of his visits to PARC was stunned by what he saw, the mouse and computer interface was truly revolutionary he felt. Xerox however had other ideas. The same Xerox leadership team that led its PARC scientists to produce breakthrough in laser printing technology in 1971 and many other innovations, seemed equally capable of squandering away the strategic advantage held by true game-changer, the personal computer. Xerox was then dubbed as the company that fumbled the future.

In 1975, Steven Sasson invented the first self-contained digital camera at Eastman Kodak. Sasson’s patent claimed an arrangement that allowed the CCD to be read out quickly (“in real time”) into a temporary buffer of random-access memory, and then written to storage at the lower speed of the storage device; essentially all modern digital cameras still use such an arrangement. His was not the first camera that produced digital images, but was the first hand-held digital camera. 37 years later, in 2012, the digital camera technology became the prime reason for Kodak’s demise. Though Kodak did eventually market both professional and consumer cameras, it did not fully embrace digital photography until it was too late.

Image Source: NY Times

In 1999, Sony launched world’s first digital music player. Sony possessed the iconic and generation-defining brand Walkman and had endorsements of virtually every heavyweight in the music entertainment industry. Yet, within few years, Apple’s ipod defined the music industry, virtually destroying the Walkman promise. Sony worried about cannibalization and was slow to react, thoughtful and diligent at every turn. If it built a music player and service that made it easy for people to share digital songs, that might hurt sales of its own music records division, which had its own profit and loss statement. Apple on the other hand had one single profit and loss statement for the entire company. Steve Jobs’s business were simple and radical. Never be afraid of cannibalizing yourself. ‘If you don’t cannibalize yourself, someone else will,’ Steve Jobs said. Result is a bed of roses for Apple, while becoming thorns under the skin for Sony.

By 2013, Nokia had lost 4/5th of its peak market capitalization in 2007. Customers were driving away in troves to competition. Nokia had ignored the glitz and glamor of Android, while it severely underestimated the new ecosystem. Microsoft lapped up Nokia’s handset business for a fraction of its value. However, unbeknownst to Microsoft, things had become so bad for Nokia that no amount of effort would be able to revive the brand. Microsoft’s own windows phone OS was in no way a challenger to Android – iOS domination. When Satya Nadella took over Microsoft from Balmer in 2014, he wrote off the entire $7.2 billion Microsoft investment in to Nokia, gave up efforts to review Microsoft’s 7 year old foray in to mobile phones and put the entire Microsoft mobile phone business on the chopping block, marking the end of a rather painful journey for Microsoft’s handheld devices business unit. This is a particularly hard pill to swallow as windows OS had won over many critics with its arguably superior interface when it launched in 2010. The initial success was short-lived and couldn’t be replicated to subsequent versions of both software and hardware.

Image Source: gsmarena

Could it all be a coincidence? The tank powered blitzkrieg, the underrated digital camera, the before-it’s-era personal computer and carry-in-your-pocket digital music player? Why do well-established, pioneering organizations lose out to maverick, new-comers? What powers the engine of growth in unconventional yet strategically sound products and technologies? Why does organizations get complacent and let upstarts overtake them? Why do leadership of these organizations fail to grasp the potential of emerging products and technologies in front of them? Isn’t guiding the organization through unknown times the primary purpose of bringing together individuals, otherwise known as leadership team? If the top organizations fail so miserably and so often, there must be some reason, some logical, rational explanation.

Answers to these questions are often hidden underneath layers of organization culture. Many modern business people, strategists and industry watchers coined the term ‘Disruptive’ and attached it to any new product, service or technology that sought to bring something new to the consumers. Disruption, in pure business terms is defined as an innovation that changes the business and industry dynamics in such a way that incumbent organizations must adapt to the change or fall by the wayside. In the face of disruptive technology or product, the incumbent organization needs to maintain its leadership status by embracing it as quickly as possible. If the organizations keep doing what worked for them in the past, they are more likely to fail as such disruptive forces demand disruption to the way of thinking and ethos of working. “Disruption” in classic business parlance describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses. That sadly is not true of how market leaders work.

Disruptive Innovation and Architectural Innovation

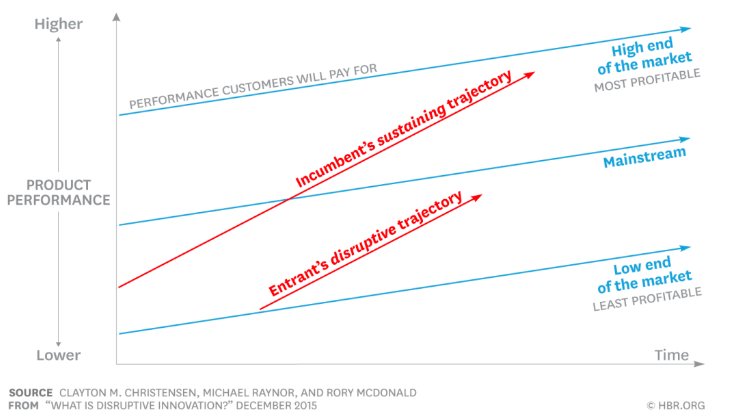

The question is: why don’t organizations adapt? Its certainly not for lack of innovation. For kodak, Sony and Xerox were all highly innovative companies with zealous management teams. Then what made them lag behind and eventually lose the fight? This is where the theory of Disruptive Innovation pioneered by Clayton M. Christensen comes in. Briefly the theory of Disruptive Innovation suggests this: Specifically, as incumbents focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, they exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others. Entrants that prove disruptive begin by successfully targeting those overlooked segments, gaining a foothold by delivering more-suitable functionality—frequently at a lower price. Incumbents, chasing higher profitability in more-demanding segments, tend not to respond vigorously. Entrants then move upmarket, delivering the performance that incumbents’ mainstream customers require, while preserving the advantages that drove their early success. When mainstream customers start adopting the entrants’ offerings in volume, disruption has occurred.

While the incumbent leader organizations are looking elsewhere, the newcomers arrive, unburdened by legacy, take a half-baked product or technology and make rapid progress carving a niche market and gaining foothold in the industry to displace the incumbent.

Image Credit: HBR.ORG

The theory of Disruptive Innovation explains as much as it leaves out. The theory is certainly valid, and elegant for the most part. Christensen has a single clear idea of how disruption happens — and recommends a solution, too: disrupt yourself before you are disrupted by someone else. However, stretching it to fit all scenarios is at best a naïve attempt at explaining the why and how of how people work.

Kodak, Sony and Xerox were all highly innovative companies, each possessing an enviable track record. The technical teams at these organizations boasted of some of the sharpest minds, while the business leaders were equally brilliant. The leadership teams at these organizations could see what lay ahead. As with innovation, the lack of vision could not be a factor. They could articulate the challenges of the times ahead and the promises of untested technologies. Yet, they were unable to put together a cohesive response strategy. It seemed no one at the helm could do the right thing. Where does this inability to lead the tanks in place of horses stem from?

The theory of Disruptive Innovation was not new in 1995 when it was first proposed, or over two decades when it was further developed. Perhaps the ideas were old, only the changing global nature of businesses made the traits ever so apparent. Or that disruption has been happening forever, we are just starting to recognize it now. Or perhaps, disruption is the normal.

When a company discovers or arrives at a successful business model often following years of painstaking work, management are given the explicit mandate to exploit that advantage to its fullest extent. This invariably means that most companies are structurally geared to manage, protect and nurture their currently successful business model. All the company’s assets – structures, operations, human resources, processes, tools and culture are geared towards doing what they have always done – protect, grow and nurture its current strengths.

It is no surprise then that swords are pulled out when there is even a shadow cast on the company’s current affairs. Any harbingers of change, which bring a radical suggestion or new idea, no matter how sound, or logically accurate, tend to be at odds with almost the entire company. This is not necessarily bad – companies do need to exploit their current positions as this is where their revenues and profits are coming from. The mistake organizations and leaders make is to focus exclusively on exploitation while ignoring most other ideas.

In the quest to understand the behavior of leaders better, theory of Disruptive Innovation does seem to fall short. Its true that Disruptive innovation changes the marketplace, however it doesn’t speak to why the incumbent organizations fail to take action? Or why the same organization with brilliant track record at innovation suddenly stops innovating?

Rebecca Henderson and Kim Clark postulated that unlike what is suggested in the theory of disruptive innovation, there are multiple points of failure where an organization fails to seize the opportunity. These points may exist all along, up and down the organization in no order. For example, in JFC Fuller’s case, almost every branch, company and division of the armed forces had little faith, mainly because many had not seen the tank in action. Questions on its size, slow pace, cramped insides, and unsightly presence were all valid, yet short-lived.

Then there are challenges about the financial viability of a product, or about its perceived value to the company, or about its future. An architectural innovation challenges an old organization because it demands that the organization remake itself. The simple explanation is that a market leader in producing printers is much likely to accept breakthrough innovations in printer ink technology as there is no real organizational stress in pursuing that product line, and highly unlikely to accept the idea for a personal computer as there is little organizational mechanism for paying attention to the innovation and nurturing it along.

Within the camera business — Canon and Nikon made the transition to digital technology successfully while Kodak could not. Was that because Kodak was hidebound and clueless about digital technology? Not remotely as Kodak entered the digital market very early and with some early successes. What killed Kodak, though, was that it hadn’t really been a photography company for a long time, rather it was a film, photo paper, and chemical company.

The message of Henderson’s work with Kim Clark and others is that when companies or institutions are faced with an organizationally disruptive innovation, there is no simple solution. There may be no solution at all. “I’m sorry it’s not more management guru-ish,” she says. “But anybody who’s really any good at this will tell you that this is hard.”

Tesla’s solar powered vehicles, Tesla’s SpaceX, Tesla’s home solar program are all examples of what happens when organizations shun perfectly valid ideas or technologies for lack of viability, and lesser known players enter in to the market to fill that small gap of that niche product. Tesla started off as a ‘niche’ EV manufacturer, in a market segment which itself was considered a joke by several top automobile manufacturers, and in little more than 1 decade, managed to claim the spot of most valued US Automobile brand ever. And this feat is even more enviable considering that Tesla manufactures all of 3 vehicles today. That is 3 vehicle models competing against 100’s of competitors’ models, using technology which is barely two decades old against almost 120 years of development in conventional gas powered automobiles.

Oil Industry has dominated the game for almost a hundred years now. Yet, the implications for the Big Oil are really very straightforward. Adapt and invest in clean fuel or simply rollover. And that is not an exaggeration by any means. The writing has been on the wall for some time now and the Oil Industry is cognizant of the same.

Image Source: Forbes

Conclusion

The thing with new, game-changing technologies, products or ideas, is that to thrive it needs to find an organization that will accept it. Adaption of any new technology has severe implications; it not only changes the organization but often times creates a new industry or segment altogether. The tank changed the modern warfare forever; Netflix ushered in an era of online streaming; personal computers took computing out of huge air-conditioned rooms to homes; iPods created an entirely new marketplace for music; and the digital cameras brought photography to 3 year old and 80 years old alike. These are all game-changers, whose potential was not unknown to their parent organizations, yet it took alien organizations to realize their full potential.

Only those organizations which are truly willing to change themselves, reorganize and adapt, re-skin and lose its earlier identity, and let that idea, or technology or product guide it to the future, those organizations mature enough to understand that immaturity is a gift, those are the organizations that create unparalleled wealth and unimaginable success stories.